Communication Processes in the Scientific Environment

O.N. Shorin

Abstract: The main means of providing access to the results of scientific research are considered. The reasons for the unavailability of scientific publications to scientists are analyzed, the process of the formation of the idea of open access is described, and the current state of affairs regarding the publication of scientists’ achievements in open access is reviewed. The study analyzes statistics that clearly demonstrate the main trends in the field of scientific communications on a global scale.

Keywords: communication processes in science, open access, scientific journals, publications, centralized subscription, open repositories, bibliometry, copyright, publishing houses, citation, Web of Science

Citation: O.N. Shorin. Communication Processes in the Scientific Environment / O. N. Shorin // Scientific and Technical Information Processing. – 2024. – Vol. 51, No. 1. – P. 21-28. – DOI 10.3103/S0147688224010039.

INTRODUCTION

The exchange of knowledge between scientists; the open discussion of applied methods, theories, and models; and the independent verification of results are some of the fundamental principles of the development of science. Initially, these functions were performed by professional scientific communities, in which researchers could openly discuss with colleagues on various topics related to a particular theory, experiment, and formulate conclusions. With the development of book printing, such discussions migrated to scientific publications, or community-distributed magazines in which articles discussing various scientific achievements were published, and any interested researcher could become familiar with them, try to confirm the provisions set out in them or refute them, using the same mechanism for the publication of scientific articles.

This practice of obtaining, confirming or refuting, and accumulating scientific knowledge has survived to this day. Moreover, over time, managers who administered funding for various fields of science began to desire to be able to measure the development of scientific areas using quantitative indicators [1]. As a result, the concept emerged that the end product of scientists’ research is published in scientific articles. Thus, the need for scientists to become familiar with scientific articles in areas of interest to them and the opportunity to publish in scientific journals have become necessary conditions for the development of scientific knowledge.

In agreement with the postulate that science has no boundaries and knowledge is accumulated in the interest of all humanity, it is obvious that for the sustainable development of science it is necessary to ensure access to scientific publications for absolutely all scientists, regardless of their nationality, political views, financial capabilities, etc.

For a long time, libraries have provided scientists with access to scientific publications by purchasing periodicals and making them available to readers. However, in the second half of the twentieth century, an irreversible process of commercialization of the scientific periodicals market began when such commercial publishing houses as Springer (Germany) and Elsevier (the Netherlands), began to buy the rights to scientific journals from small organizations. They combined these journals into packages, inviting libraries to purchase these packages as a whole, which forced libraries to buy not only those publications in which they were interested but all of the others included in the package as well. This inevitably led to an increase in subscription costs. This approach to increasing the size of packages and their cost is called the Big Deal [2]. In particular, according to research [3], the price of subscription to scientific journals in the USA from 1984 to 2001 increased by 651.6% for journals on zoology, by 614.0% for journals on chemistry and physics, and by 578.6% for journals on medicine.

A paradoxical situation has arisen that experts call “double payment,” when the state allocates money for research resulting in publications in scientific journals and then the state is forced to purchase these journals from commercial companies to provide scientists with up-to-date information [4].

Due to the widespread availability of high-speed internet connections, leading publishers, instead of packages of printed versions of magazines are now offering subscriptions to access electronic versions of magazines. Libraries and research institutions have begun to join consortia to purchase subscriptions to the packages that they needed for the benefit of the consortium. This was explained by the following logic: the larger the size of the consortium, the lower the subscription cost for an individual member of the consortium. Scaling this logic could ultimately lead to the emergence of a single operator in the country that would purchase subscription access for the benefit of all scientific organizations in the country.

Since 2005, within the framework of federal target programs to support priority areas of the development of the scientific and technological complex of the Russian Federation, the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation has provided targeted funding for subscriptions to foreign electronic resources. The following were described as executors of government contracts to provide access to foreign scientific information during different periods [5]:

- in 2005–2013, the NEICON consortium;

- in 2014–2019, the State Public Scientific and Technical Library (SPNTL) of Russia;

- from 2020 to the present, the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (RFBR), which, by Decree of the Government of the Russian Federation of July 29, 2022 No. 1357, was renamed the Russian Center for Scientific Information (RCNI).

According to the RCSR reports, the cost of licensing and sublicensing agreements for access to electronic publications and scientific information resources in the interests of Russian scientists amounted to 3,555.88 million rubles in 2020 [6], 3733.7 million rubles in 2021 [7], and 4918.87 million rubles in 2022 [8].

These data show that the cost to the government of providing access to electronic resources is increasing from year to year. In addition, by acquiring access to publications and not the publications themselves, new risks appear, which in the legal literature are called end of ownership [9], whereby access to certain subscribed electronic resources are closed due to various factors: for example, the geopolitical situation, from sanctions imposed by some countries on others, from lack of funding, etc.

This contradicts the original principles of the development of science in the framework of all humanity: openness, limitlessness, comprehensive, and unhindered access to current scientific information. In addition, most scientific research is funded by the government, such that the results of this research, in particular scientific publications in journals, are in he public domain and should be available to everyone. Here, a movement for the provision of open access to scientific publications arose and developed [10].

The journal crisis, of course, had a decisive impact on the development of open access ideas, but, in addition to this, experts have identified several other types of reasons: economic and managerial ones, the development of electronic publishing and new network technologies, and social motives [2].

OPEN ACCESS

It is generally accepted that the starting point for the movement to open access for scientific publications was the Budapest Open Access Initiative, adopted on February 14, 2002 following a conference convened by the Open Society Institute Foundation [11]. The initiative proposed using modern technologies, in particular the internet, for free publication by scientists of the fruits of their labors for the unhindered dissemination of new knowledge.

The Budapest Initiative was intended primarily to provide access to peer-reviewed journal articles for everyone. However, it also making other materials open access, such as non-peer-reviewed preprints, which would allow scientists to quickly publish their results and receive feedback from peers.

To achieve this goal, two complementary tools were proposed [12]:

creation of open archives in which scientists could freely post their publications, documents, data, etc. It was understood that along with this, software tools would be developed that would allow the exchange of information between archives, aggregation of metadata, and searches in a distributed system of open archives;

creation of a new generation of alternative journals intended to disseminate knowledge without any restrictions. To provide financial support for such journals, it was proposed to use donations from individuals and foundations, attract funding from universities and the state, and develop a system of additional paid services that would be provided by journals based on scientific publications.

To date, the Budapest Open Access Initiative has been signed by 1573 organizations and 6765 individuals.

On October 22, 2003, in furtherance of the ideas of the Budapest Open Access Initiative [13], the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Scientific and Humanitarian Knowledge was published, which formulated the requirements for open access publications and actions aimed at supporting the further development of open access principles access.

The Berlin Declaration was originally signed by 19 representatives of various scientific and research organizations [14]. They agreed that the Berlin Open Access Conference would be held annually. At the Berlin Conference, which took place on June 6–7, 2023, all delegations present at the meeting adopted a statement consisting of the following points [15]:

The global transition to open access must move at a much faster pace.

Inequality is incompatible with scientific publishing.

Academic self-governance is an imperative in scientific publishing.

The author’s choice to grant a set of rights, as well as the copyright to publish, must be fully supported by legal instruments and not be limited by publishing houses.

One argument made by scientists for making their scientific publications open access is that articles published in open access receive more citations than articles that are published in subscription journals. Some studies have confirmed this assumption [16]. However, there are scientists who have come to opposite conclusions [17]. The fact is that in different fields of science, information becomes outdated at different rates, which is why approaches to the use of citations vary depending on the thematic specialization [18]. Therefore, the result of the given study are greatly influenced by the choice of the time interval during which the citation of publications is analyzed. Some scientists suggest that articles published in open access have a higher initial citation rate, but over time this figure 1 levels off [19], as it is generally accepted that articles published in journals available by subscription are more authoritative and for this reason they are cited more often [20].

Data Available through Open Access

The Budapest Open Access Initiative initially declared that it was necessary to develop two areas: open access archives and a new type of scientific journals for publishing articles [21]. Subsequently, it was found that for managers administering the distribution of finances in various areas of scientific research, access to bibliometric databases that store information about the citation of scientific articles of some scientists by others, are of great interest [22]. In this regard, with respect to data available through open access, there are three main types:

scientific archives, which primarily house nonpeer-reviewed publications and related data;

bibliometric databases; and

publications in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Scientific Archives

The publication of an article in a scientific journal is a long and labor-intensive process, as in high-quality journals, the article undergoes strict peer review (excluded from consideration are so-called “predatory” journals that are willing to quickly publish an article for a fee without peer review or using only self-review [23]). Most often, reviewing takes several months, sometimes this period can increase to several years [24]. In addition, at the reviewing stage, up to 70% of manuscripts received by the editor may be eliminated [25]. In this regard, scientists need a mechanism through which they can quickly publish their results. This mechanism is the publicly accessible open archives of scientific information, or open access repositories.

In such repositories, scientists can place preprints to secure their leading position in a certain area of research, in the form of articles that have not yet been peer-reviewed and therefore not published (deposits), the data necessary for reproducing and verifying their research, and audio and video materials that may be impossible to publish in scientific journals.

Traditionally, repositories are usually divided into [26]:

- institutional: repositories created by research organizations to house materials from their employees. Such repositories are created by institutions to confirm the significance of the institute and to record and control the scientific research carried out in the organization;

- thematic: repositories that accumulate materials on a specific topic, regardless of the scientist’s place of employment; and

- general purpose: repositories that are not limited to any topic and are not associated with an institution.

The Open Archives Initiative (OAI) standards have been developed that the repository must comply with to ensure interoperability with other systems, which will ensure the effective dissemination of information, as well as the creation of services based on content stored in scientific archives. One of the main standards of this initiative is a protocol for collecting metadata, the Protocol for Metadata Harvesting (OAI-PMH) [27]. Using this protocol, it is possible to aggregate data stored in various repositories and organize a search with subsequent access to the data, regardless of the repository that they are physically located in, thereby implementing a hybrid model for the functioning of scientific archives: distributed storage with dedicated central nodes, performing indexing and searching in various repositories.

Several software platforms have been developed that can be used to organize and administer an open repository. Most of these platforms are standards compliant with OAI, so anyone who wants to organize a scientific archive can choose the best-suited platform. Among the most common software platforms are: DSpace, Eprints, WEKO, and Digital Commons [28].

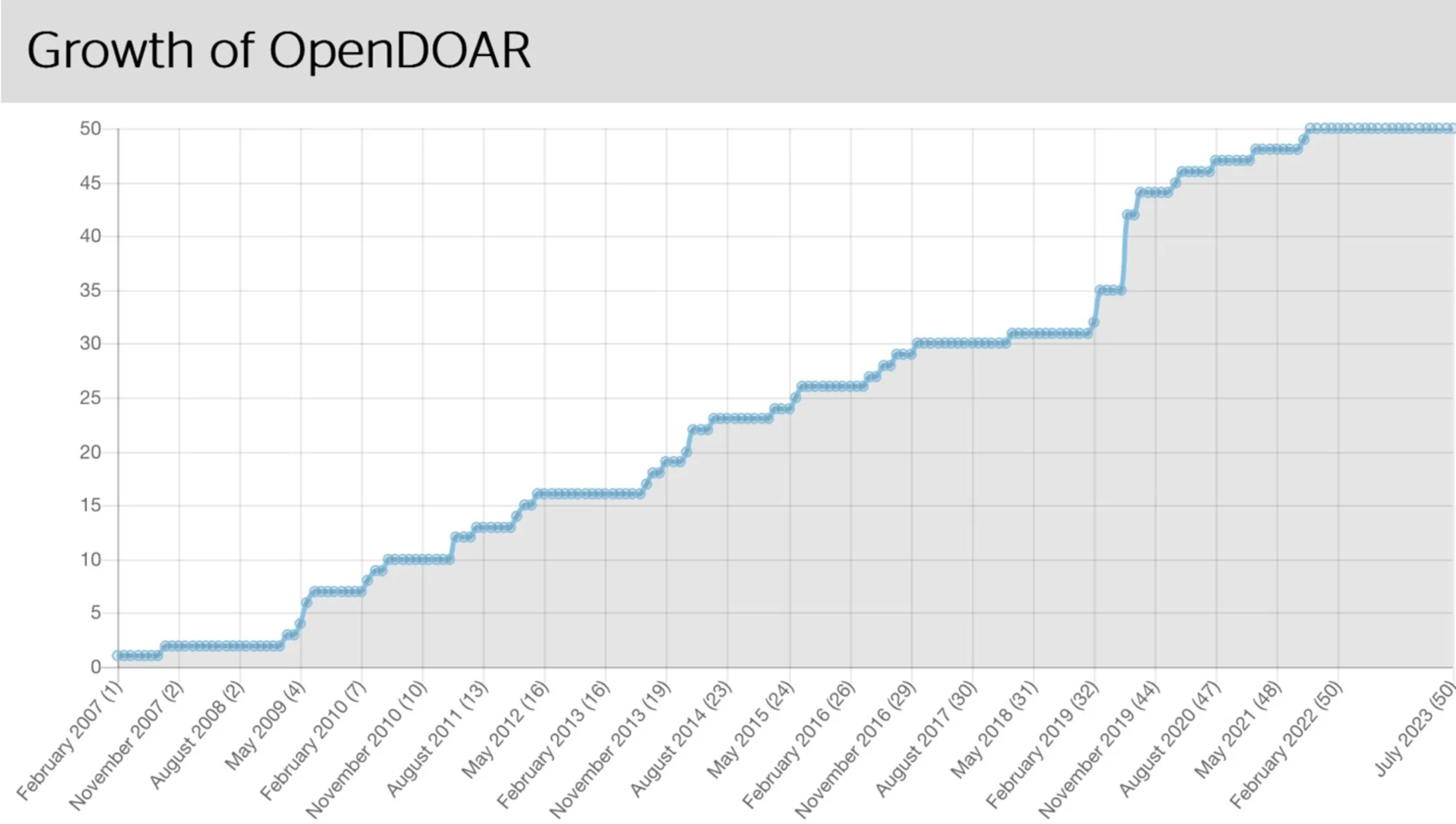

There are also two well-known registries of open repositories designed to register scientific archives, collect information about them and disseminate this information to the scientific community: Registry of Open Access Repositories (ROAR) [29] and Directory of Open Access Repositories (OpenDOAR) [30]. As of July 21, 2023, ROAR contains information on 4725 repositories, and OpenDOAR has information on 6036. According to ROAR, there are 67 repositories in Russia, and according to OpenDOAR, there are 50. The dynamics of growth of Russian repositories in OpenDOAR shown in the figure 1.

According to OpenDOAR, two-thirds (66%) of repositories in Russia operate under the control of the software platform DSpace; 41 repositories contain information on social sciences; 38 on medical sciences; 36 on humanities, mathematics, and technological studies; and 35 on arts and engineering [31].

In 2011, a study was conducted on the attitude of scientists towards open repositories of scientific information [32], which showed that scientists prefer to learn about the research of their colleagues from open scientific archives, although they are not very keen to publish their own work in them. This is partly because scientists place a higher value on their publications in scientific journals that have been peer-reviewed than on the information they make available on their own without prior peer review. As a result, repositories are secondary to publications in scientific journals, although they have the potential to develop as a platform for the exchange of scientific data, which is not taken into account in reporting but is of interest for information saturation [33].

Bibliometric Databases

Over the last decade, through the efforts of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Russian Federation and various foundations issuing grants for research, our country has built a system for assessing scientific work that relies heavily on bibliometric indicators of individual employees and organizations as a whole. In accordance with this system, it is customary to take into account various indicators: the number of publications, the number of co-authors, the number of affiliations, the Hirsch index, the impact factor (quartile, decile, percentile, etc.) of the journal in which an article is published, the number of links to published articles, lack of self-citations, etc. All these indicators were selected from two non-Russian databases: Web of Science (owned by Clarivate) and Scopus (owned by Elsevier), which were available to all scientific organizations in Russia through the mechanism of national and centralized subscription.

These commercial databases, which are owned by non-Russian companies, have been periodically criticized due to their focus mainly on journal articles and insufficient coverage of other scientific publications, but methods for assessing the activities of organizations, dissertation councils, grant applications, and reports developed by The Ministry of Education and Science of Russia, the Higher Attestation Commission, and grant funds are based on the use of precisely these databases because in 2012 the Decree of the President of the Russian Federation of May 7, 2012 No. 599 “On measures to implement state policy in the field of education and science” was signed, in according to which it was necessary to ensure “an increase by 2015 in the share of publications by Russian researchers in the total number of publications in world scientific journals indexed in the WEB of Science database to 2.44 percent.”

There was practically no alternative to the use of the Web of Science as the main source of bibliometric information. However, in May 2022, access to this database was closed to scientists from Russia, and in January 2023, access to the Scopus database was also stopped [34]. Thus, the issue of using open bibliometric systems has become more acute.

It is necessary to mention that in 2010 the OpenCitations project appeared, the main goal of which was to make possible the free publication of bibliography in a format convenient for machine processing [35]. The main achievement of this project is the creation, maintenance, and filling of an open repository of data on citations in scientific publications. At the initial stage of preparation of this repository, scientific articles on medicine were used, which were available in the public domain. Subsequently, software was developed to automate the process of filling this repository. Since April 2017 OpenCitations became one of the six founders of the Initiative for Open Citations (I4OC), the main goal of which is to ensure the accessibility of citation data, taking into account the principles of structure, openness, and separability [36].

Here, structured refers to the fact that data on each publication and its citations are presented in a machine-readable format, so that the information can be processed by software. The principle of separability means that citation data is available and can be analyzed without the need to access the text of the articles in which those citations are given. Openness means that citation data are available to everyone without restriction and can be used to create higher-level services.

Partly thanks to this approach to the use of data and the developments of certain systems to create new services, over the last twenty years, a number of polythematic bibliographic databases have appeared that differ from each other in terms of coverage, types of stored data, and functionality provided. In particular, the following systems can be distinguished: Google Scholar (year of foundation, 2004), AMminer (2006), Lens (2013), Scilit (2014), Semantic Scholar (2015), Microsoft Academic (2016), Dimensions (2018), scite_ (2019), MyRA (2019), Exaly (2022), and OpenAlex (2022). According to a review of the functionality and content of these databases, systems such as Lens, Dimensions, and OpenAlex contain information on citation lists, which, as already noted, is important for bibliometric analysis [37].

Research indicates that as early as 2021, the amount of citation data available using open data systems will reach parity with data from the data systems Web of Science and Scopus [38]. Thus, a free, open alternative to proprietary systems has appeared in the world, with the help of which it is possible to solve various bibliometric problems, in particular, to assess the publication activity of individual employees, teams of authors, or entire organizations and institutions.

Publications in Peer-Reviewed Journals

The rise in subscription prices for publishers is explained by the fact that, in addition to the costs of printing services for the distribution of printed materials and maintaining the network infrastructure for subscription to electronic versions of journals, they are forced to spend huge amounts of money on reviewing articles that are received by editorial offices. Since the number of articles grows from year to year [39], the cost to publishers of ensuring the quality of published articles increase, which is compensated for by the increase in subscription costs.

The work of reviewers, as well as teams of editorial boards of journals, must be paid. If a publisher publishes all journals open access, losing the opportunity to receive money for the printed version or for providing access to the electronic version, then it will be forced to make money in some other way.

One such way is to provide services for translating articles into other languages for publication in so-called translation journals. There is an assumption that an article in English will be read and, accordingly, cited by a much larger number of people than the same article, for example, in Russian. In this regard, in parallel with journals in Russian, publishing houses sometimes create exactly the same journals in English, charging authors a fee for translating an article from Russian into English and publishing the translated article in the English version of the journal. Because the translation of the article is paid for by the author, who either receives a salary from the state or uses grant money received by him for this purpose, then instead of the already mentioned problem of double payment for the publication of an article and access to it, a triple problem arises: the state pays for the work of the scientist who publishes the article, the translation of this article into a foreign language for the translated version of the journal, and a subscription to access the electronic version of the journal in which the translated article will ultimately be published.

Having identified the mechanism for receiving money from authors for translating their articles into other languages, in conditions of open access, publishing houses quite logically shift the burden of costs from consumers of their products (readers) to content providers for their journals (authors) [40]. There are, of course, publishers that do not charge money from either readers or authors (the so-called “diamond” or “platinum” type of open access [11]), but often publishers require authors to pay an article processing charge in exchange for their article being published in open access [41]. The cost of this service in high-ranking journals is quite high, reaching several thousand dollars per article [42]. The state is forced to pay this amount for the article to be made publicly available.

What is open access? The Budapest Initiative defines open access as access that allows the free reading of an article, as well as its secondary use: indexing content, downloading an article using software, or using content for any other legal purpose. There are other definitions that interpret open access only as the ability to read scientific literature online [43]. The third type of open access definition requires that open access articles be digital, accessible online, and free [44].

Taking advantage of the fact that the range of formulations of the concept of open access is quite wide, publishing houses require authors to sign their own versions of licensing agreements, which clearly state who has what rights to the published article. Experts conditionally divide these license agreements into several types [45]:

- libre: the user can read the article, as well as reuse it by indexing it, downloading it using software, archiving it, and working with the text in any legal way;

- gratis: the user can only read the article online;

- gold: the article is published in the so-called “open journal,” a journal in which the user can read all of the open articles on the publishing house’s website;

- green: the article is published in a journal that is available for a fee, but the author is allowed to independently publish this article in an open repository;

- bronze: the article is available on the publisher’s website, but there is no document clearly describing the mode of its use;

- hybrid: the article is published in a journal that is available for a fee, but the publisher makes it freely available under an open license; and

- deferred: this type is similar to the hybrid type, but with one difference, namely, that the publishing house does not place the article in the public domain immediately but after a certain time, which is called the embargo period.

Research shows [45] that 27.9% of articles feature some type of open access. Moreover, the majority (58%) of these articles were published using the bronze type, the hybrid type was used in 12.9% of articles published in open access, the gold type was used in 11.5% of articles, and the green type was used in 17.2%.

To streamline the open access publishing market, cOALition S, consisting of organizations that fund scientific research, was formed in the European Union in 2018 [46]. This coalition advocates for all government-funded research results to be made publicly available. On September 4, 2018, the coalition published Plan S, according to which, by 2020, all scientists receiving government research money are required to post their results in the public domain [47].

Plan S was developed according to 10 principles [48].

Authors retain the rights to their publications; copyrights are not transferred to publishers.

Criteria for open access journals and platforms must be defined.

The creation of open access platforms should be encouraged by coalition members.

Researchers do not have to pay for the publication of materials; sponsors or organizations in which these researchers work must pay for them.

The fee should be standardized and limited.

There must be an open access policy and everyone must act in concert within that policy.

For books and monographs, the effective date of Plan S may be delayed.

The importance of open repositories is recognized.

The hybrid type of open access is considered noncompliant with Plan S.

Coalition members must monitor compliance with Plan S and punish violations.

Plan S has both supporters and opponents. Its main opponents, of course, are publishing houses, which claim that the implementation of Plan S will lead to a deterioration in the quality of peer review, a decrease in the number of publications, and a reduction in the dissemination of scientific research results. Surprisingly, Plan S has been opposed by some academic researchers, who claim that they support the idea of open access, but also believe that the proposed plan has weaknesses [49]. Outside Europe, attitudes towards Plan S also vary greatly [50].

CONCLUSIONS

Scientific research has always implied openness, as only those results that can be freely discussed, criticized, reproduced by other scientists, and used in subsequent research can be considered scientific. Publishers that monopolize the market for scientific periodicals certainly contribute to the process of improving the quality of scientific publications, but at the same time, they create barriers to access to them, which contradicts the original principles of the dissemination of scientific knowledge.

At this stage, we are observing a certain transition process when the scientific community is trying to develop new approaches to the accumulation and exchange of scientific achievements using modern technologies [51]. At the same time, the interests of many players are affected, which has led to certain conflicts in this area. Resolving the accumulated problems will most likely require a significant transformation at the interstate level of established rules, policies for allocating funding for research, ethics and culture of scientific communications, copyright legislation, etc.

FUNDING

This work was supported by ongoing institutional funding. No additional grants to carry out or direct this particular research were obtained.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author of this work declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Sterligov, I.A., Progress criterion: Why did Russia need Web of Science and how can it do without it?, N + 1, 2022. https://nplus1.ru/blog/2022/05/24/no-wos-russia . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Zemskov, A.I. and Shraiberg, Ya.L., Open access information systems: Reasons and history of appearance, Nauchn. Tekh. Bibl., 2008, no. 4, pp. 14–29.

- Albee, B. and Dingley, B., U. S. periodical prices 2001, Am. Libr., 2001, no. 2. https://www.ala.org/ala/alonline/selectedarticles/periodicals01.pdf . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Kosyakov, D.V., Russian science in open science: State-of-the-art and trends, Sbornik tezisov dokladov Mezhdunarodnoi nauchno-prakticheskoi konferentsii Nauka, tekhnologii i informatsiya v bibliotekakh (Libway-2019) (Collection of Abstracts of the Reports at the Int. Sci.-Pract. Conf. on Science, Technologies, and Information in Libraries (Libway-2019)), Irkutsk, 2019, Artem’eva, E.B., Ed., Irkutsk: Gos. Publichnaya Nauchno-Tekhnicheskaya Biblioteka Sib. Otd. Ross. Akad. Nauk, 2019, pp. 107–110.

- Glushanovskii, A.V., Creating and evolution centralized scientific journals remote access system for information support of Russian scientific research, Nauka Nauchnaya Inf., 2022, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 61–75. https://doi.org/10.24108/2658-3143-2022-5-2-2

- Report about the results of activity of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research and use of federal assets in 2020. https://www.rfbr.ru/rffi/getimage/Otchet_o_rezul'tatakh_deyatel'nosti_federal'nogo_gosudarstvennogo_byudzhetnogo_uchrezhdeniya_%22Rossiiskii_fond_fundamental'nykh_issledovanii%22_i_ispol'zovanii_zakreplennogo_za_nim_federal'nogo_imushchestva_za_2020_god.pdf?objectId=2120670&v=1690533102814 . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Report about the results of activity of the Russian Foundations for Basic Research and use of federal assets in 2021. https://www.rfbr.ru/rffi/getimage/Otchet_o_rezul'tatakh_deyatel'nosti_federal'nogo_gosudarstvennogo_byudzhetnogo_uchrezhdeniya_%22Rossiiskii_fond_fundamental'nykh_issledovanii%22_i_ispol'zovanii_zakreplennogo_za_nim_federal'nogo_imushchestva_za_2021_god.pdf?objectId=2127682&v=1690533102814 . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Report about the results of activity of the Russian Foundations for Basic Research and use of federal assets in 2022. https://www.rfbr.ru/rffi/getimage/Otchet_o_rezul'tatakh_deyatel'nosti_federal'nogo_gosudarstvennogo_byudzhetnogo_uchrezhdeniya_%22Rossiiskii_tsentr_nauchnoi_informatsii%22_i_ispol'zovanii_zakreplennogo_za_nim_federal'nogo_imushchestva_za_2022_god.pdf?objectId=2132838&v=1690533102813 . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Perzanowski, A. and Schultz, J., The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy, Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2016.

- Brichkovskii, V., Initiation of open access in information support of innovation activity, Nauka Innovatsii, 2019, no. 12, pp. 76–79.

- Yurchenko, S.G., “Diamond” open access in the conditions of self-insulation: Implementation of actual approaches in the SMC Bulletin, Vestn. Nauchn.-Metodicheskogo Soveta po Prirodoobustroistvu Vodopol’zovaniyu, 2020, no. 17, pp. 7–16. https://doi.org/10.26897/2618-8732-2020-17-7-16

- Declaration of Budapest Open Access Initiative. https://www.budapestopenaccessinitiative.org/read/ . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Berlin declaration. https://openaccess.mpg.de/Berlin-Declaration . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Berlin Declaration on open access to knowledge in the sciences and humanities. https://openaccess.mpg.de/67605/berlin_declaration_engl.pdf . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Final Statement of the 16th Berlin OA Conference. https://openaccess.mpg.de/b16-final-statement?c=318911 . Cited July 28, 2023.

- Tennant, J.P., Waldner, F., Jacques, D.C., Masuzzo, P., Collister, L.B., and Hartgerink, C.H.J., The academic, economic and societal impacts of Open Access: an evidence-based review, F1000Research, 2016, vol. 5, p. 632. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.8460.3

- Davis, P.M., Open access, readership, citations: A randomized controlled trial of scientific journal publishing, FASEB J., 2011, vol. 25, no. 7, pp. 2129–2134. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.11-183988

- Moskaleva, O.V. and Akoev, M.A., Forecast of the development of russian scientific journals: Open access journals, Nauka Nauchnaya Inf., 2021, vol. 4, nos. 1–2, pp. 33–62. https://doi.org/10.24108/2658-3143-2021-4-1-2-29-58

- Komaritsa, V.N., Benefits of using open access: Citation analysis, Autom. Doc. Math. Linguist., 2022, vol. 56, no. 4, pp. 197–202. https://doi.org/10.3103/S0005105522040045

- Chernova, O.A., The effect of open access on scientometric indicators of Russian economic journals, Upravlenets, 2022, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 69–82. https://doi.org/10.29141/2218-5003-2022-13-4-6

- Yudina, I.G. and Fedotova, O.A., Repositories of open access scientific publications: History and prospects of development, Inf. O-vo., 2020, no. 6, pp. 67–79.

- Mokhnacheva, Yu.V. and Tsvetkova, V.A., Russia in the global array of scientific publications, Herald Russ. Acad. Sci., 2019, vol. 89, no. 4, pp. 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1134/S1019331619040075

- Malakhov, V.A., The open science movement: Causes, state of the art, and prospects for development, Upr. Naukoi: Teoriya Prakt., 2021, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 118–133. https://doi.org/10.19181/smtp.2021.3.3.6

- Science in open access: Scientists in favor and opposed. http://libinform.ru/read/articles/Nauka-v-otkrytom-dostupe-Uchenye-za-i-protiv/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Shraiberg, Ya.L. and Zemskov, A.I., Open access models: History, types, peculiarities, and terminology, Nauchn. Tekh. Bibl., 2008, no. 5, pp. 68–79.

- Zasurskii, I.I., Sokolova, D.V., and Trishchenko, N.D., Open access repositories: Functions and trends of development, Nauchn. Tekh. Bibl., 2020, no. 9, pp. 121–142. https://doi.org/10.33186/1027-3689-2020-9-121-142

- Rozhdestvenskaya, M.Yu., Repositories as an implementation of ideas of open access to publications: Approaches to classification, Bibliosfera, 2015, no. 2, pp. 86–94.

- OpenDOAR statistics: Software platforms overview. https://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/view/repository_visualisations/1.html . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Registry of Open Access Repositories. http://roar.eprints.org . Cited July 31, 2023.

- OpenDOAR. https://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/opendoar/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- OpenDOAR: Browse by country and region. https://v2.sherpa.ac.uk/view/repository_by_country/Russian_Federation.default.html . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Mulligan, A. and Mabe, M., The effect of the Internet on researcher motivations, behaviour and attitudes, J. Doc., 2011, vol. 67, no. 2, pp. 290–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220411111109485

- Trishchenko, N.D., Otkrytyi dostup k nauke. Analiz preimushchestv i puti perekhoda k novoi modeli obmena znaniyami (Open Access to Science: Analysis of Advantages and Paths to Transit to the New Model of Knowledge Exchange), Moscow: Assotsiatsiya Internet-Izdatelei, 2017.

- Khokhlov, A., Scopus database ceased being available in Russia. https://poisknews.ru/science-politic/akademik-ran-aleksej-hohlov-baza-dannyh-scopus-perestala-byt-dostupnoj-v-rossiidrugih-czelej/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- OpenCitations. http://opencitations.net/about . Cited July 31, 2023.

- An initiative to open up citation data. https://i4oc.org/#goals . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Gureev, V.N. and Mazov, N.A., Increased role of open bibliographic data in the context of restricted access to proprietary information systems, Upr. Naukoi: Teoriya Prakt., 2023, vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 49–76. https://doi.org/10.19181/smtp.2023.5.2.4

- Martín-Martín, A., Coverage of open citation data approaches parity with Web of Science and Scopus. https://opencitations.word-press.com/2021/10/27/coverage-of-open-citation-data-approaches-parity-with-web-of-science-and-scopus/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Open science: Path to the inevitable. http://libinform.ru/read/articles/Otkrytaya-nauka-put-v-neizbezhnost/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Grinberg, M.L., Hidden pitfalls of the open access publication system: Opinions in different countries, Nauchnaya Periodika: Probl. Resheniya, 2014, no. 2, pp. 11–20.

- Razumova, I.K., Litvinova, N.N., Shvartsman, M.E., and Kuznetsov, A.Yu., Attitude to open access in Russian scholarly community: 2018. Survey results and analysis, Nauka Nauchnaya Inf., 2018, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 6–21. https://doi.org/10.24108/2658-3143-2018-1-1-6-21

- Björk, B.C., Open access to scientific publications — An analysis of the barriers to change?, Inf. Res., 2004, no. 9, p. 170. http://hdl.handle.net/10227/647 . Cited August 31, 2023.

- Willinsky, J., The nine flavours of open access scholarly publishing, J. Postgraduate Med., 2003, no. 49, pp. 263–267.

- Matsubayashi, M., Kurata, K., Sakai, Yu., Morioka, T., Kato, S., Mine, S., and Ueda, S., Status of open access in the biomedical field in 2005, J. Med. Libr. Assoc.: JMLA, 2009, vol. 97, no. 1, pp. 4–11. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.97.1.002

- Piwowar, H., Priem, J., Larivière, V., Alperin, J.P., Matthias, L., Norlander, B., Farley, A., West, J., and Houstein, S., The state of OA: A large-scale analysis of the prevalence and impact of open access articles, Nauka Nauchnaya Inf., 2019, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 228–247. https://doi.org/10.24108/2658-3143-2019-2-4-228-247

- What is cOAlition S?. https://www.coalition-s.org/about/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Why Plan S?. https://www.coalition-s.org/why-plan-s/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Plan S principles. https://www.coalition-s.org/plan_s_principles/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Plan S: Scientists support, but do not want to risk. http://libinform.ru/read/articles/Plan-S-uchyonye-podderzhivayut-no-ne-hotyat-riskovat/ . Cited July 31, 2023.

- Rabesandratana, T., Will the world embrace Plan S, the radical proposal to mandate open access to science papers?: China appears to embrace Europe-led plan, but other countries are reluctant, Science, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw5306

- Litvinova, N.N. and Razumova, I.K., Attitude to open access in Russian scholarly community 2020: Two years later, Nauka Nauchnaya Inf., 2020, vol. 3, no. 4, pp. 226–260. https://doi.org/10.24108/2658-3143-2020-3-4-243-277